Hawaii | Big island

Hawaii, USA

Winter 2024

Deep in the Pacific Ocean lies the tallest mountain in the world. At the seafloor, lava carves inevitable trenches across the black landscape, leaving rift zones that boil with magma. Closer to the surface, humpback calves and sea turtles come up for air before submerging, no doubt to escape the seabirds that wheel overhead. Dense rainforests, savannas, and hot deserts give way to subarctic tundra and a polar ice cap mounted at the peak of Mauna Kea, Big Island: 13,803 ft above sea level, 33,500 ft from its base.

Unlike other isolated, touristy regions, where humans and plant growth are locked in an arms race of creating and destroying clever infrastructure, Hawaiians live with their land. Wild chickens and pheasants pay little attention to people and their property lines; the Kona airport is mostly wooden and open air. Endangered species take long naps on the beach while being celebrated with bumper stickers and road signs.

The island feels immune to the rush of modern living and social media algorithms. Surfboards have permanent residence on rusted 2008 Toyota Tacomas. Children speak ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi to their parents in grocery stores.

It’s hard to believe this volcanic terrarium has any relation to the United States. It’s hard to believe that it should. But by some miracle, despite invasion by empires and tourists, Hawaiians have extended their land to people like me. Here’s my attempt at documenting the ecological haven of Big Island.

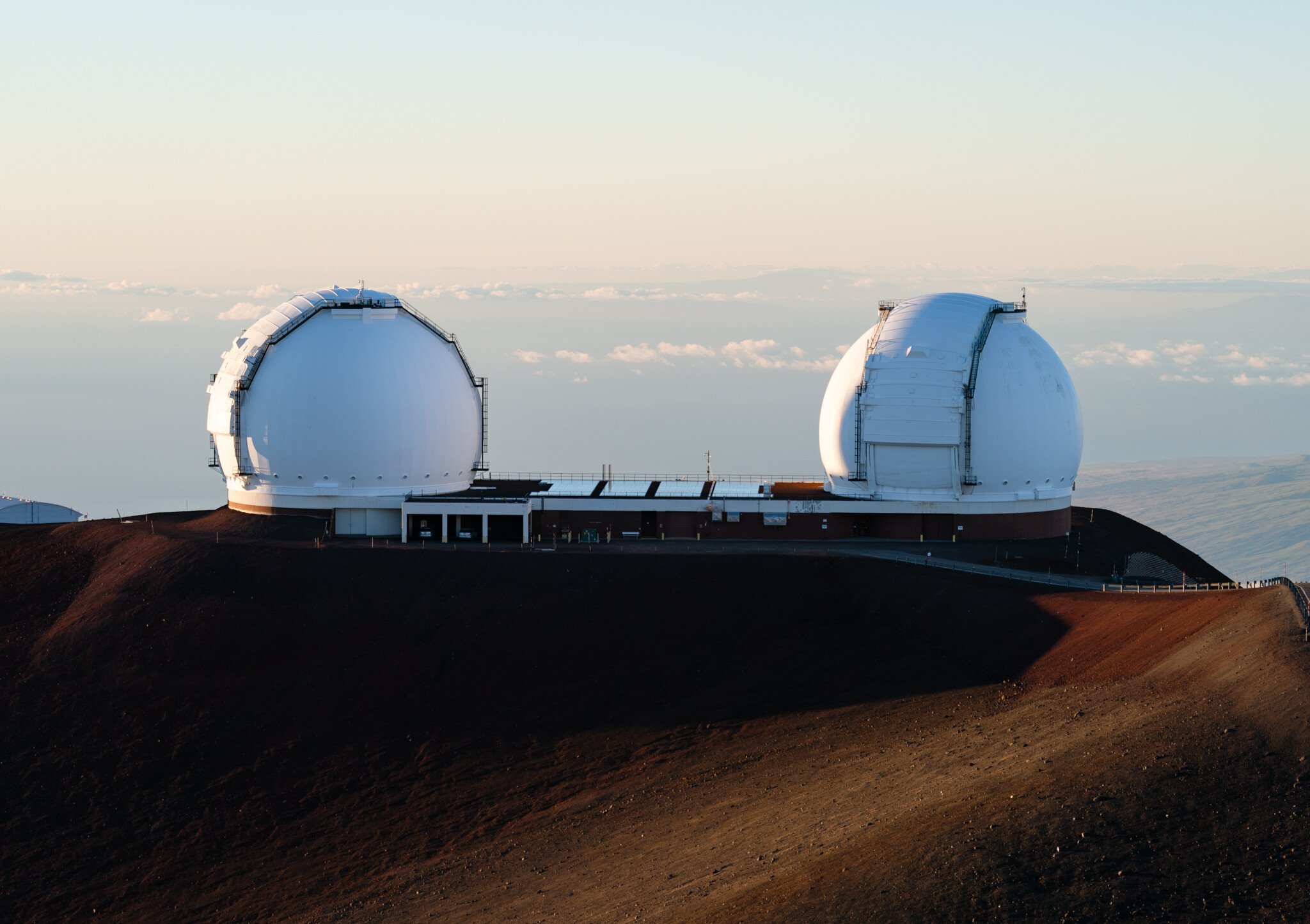

Mauna Kea

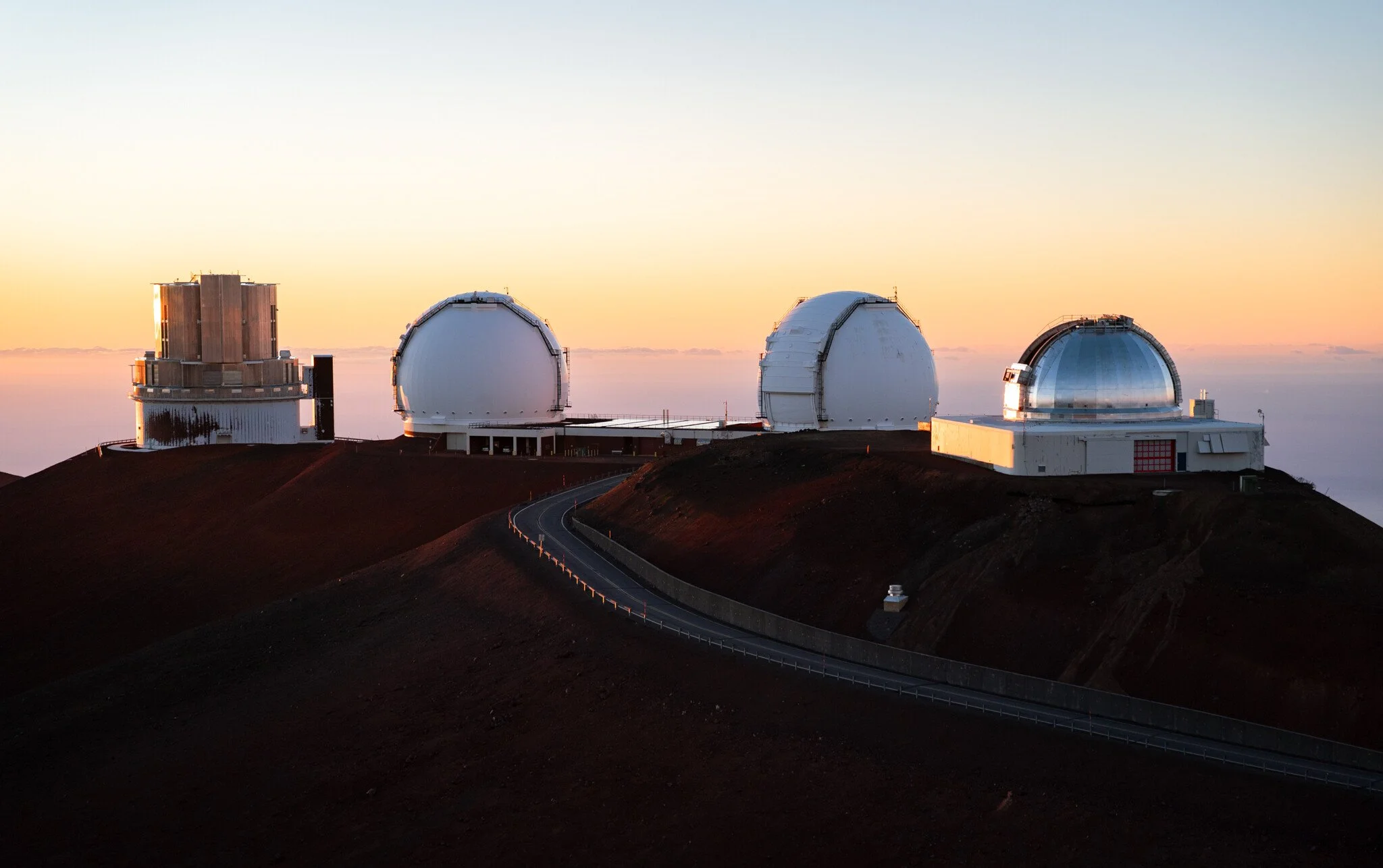

Bottom Left: James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, Smithsonian Submillimeter Array, Subaru Telescope, Keck I & II, NASA Infrared Telescope Facility

NASA Infrared Telescope Facility

My partner’s Apple Watch reads 180 bpm on my wrist. On my left, Jeeps grind their way up the pitted road, passengers looking at me with concern. They yell out the window, asking if I’m alright. I give a thumbs up. On my right, the ground falls away. It doesn’t stop until it hits the ocean, a faint glimmer miles away.

Over time, my breathing slows, the tingling in my extremities fades, my vision returns to normal. Oxygen is at 60% sea level, but I’ve avoided altitude sickness. I crank my Jeep back to 4WD.

The summit of Mauna Kea is frigid and alien. After driving from the coast to 13,800 feet in four hours, I gasp for air walking up an incline. But the view is laid out on a panoramic platter: Oxidized red soil, just like on Mars, dotted with observatories from eleven different countries. The setting sun illuminates the cloud inversion and gives the reflective domes a pristine space-age white that I’ve only seen on an IMAX screen, typically on an object hurtling through space and usually accompanied by an explosion (See: Matt Damon blown backwards growing potatoes on Mars).

As night falls and Venus appears as the first bright celestial object, the telescopes begin to rotate slowly, controlled by astronomers working remotely in Hilo and Waimea. Although the rangers herd us off the summit after sunset, I settle at a trailhead a few switchbacks down. Making sure my headlamp is switched to red light to protect the other photographers in the area, I pick my way off-trail, looking for an ideal spot to set up my tripod and stargaze. Now, breathing’s a little easier.

Leftmost: Gemini North Telescope

The Observatories

Keck I & Keck II: Previously the largest optical telescope, it has performed spectroscopy of exoplanets, proved the existence of Sagittarius A, and estimated the universe’s expansion rate.

Subaru Telescope: A leader in wide-field astronomy, this optical and near-infrared telescope features a single 27 ft mirror and maps dark matter distribution and detects distant galaxies.

James Clerk Maxwell Telescope: Observes submillimeter light, useful for detecting cold gas and cosmic dust clouds.

Smithsonian Submillimeter Array: Similarly observes submillimeter light across eight antennas.

Gemini North Telescope: Paired with its twin Gemini South Telescope in Chile, the two observe the entire celestial sphere at once.

Snowcone

North view from the summit of Mauna Kea

Mauna Kea’s shadow projects onto the sky during sunset. Cinder cones, formed from lava erupting out of volcanic vents, pile in the distance. They’re 4,500-250,000 years old. The distance is hard to judge - one of the most transparent atmospheres on Earth reduces haze to nothing.

Up here, the alpine desert biome is incredibly harsh. Low oxygen, freezing temperatures, and UV exposure means virtually no life can survive.

Wildlife

The Hawaiian Green Sea Turtle. Previously critically endangered with only 37 left, conservation efforts and huge fines (USD $50,000 for touching one) have brought the population back to 4000 nesting females. This one has hauled out to bask on the beach. It napped almost the entire time I was there, stopping only to yawn.

The Muscovy Duck. I found this male by a small wetland in the south of Big Island, by a black sand beach.

The Japanese White-Eye. Their gender is almost indiscernible from plumage. This particular one was flitting about a palm tree in Kona, not too far from the coast.

Both are non-native to Hawaii. The duck may have been introduced by accident; the White-Eye was brought intentionally as pest control and quickly became an invasive species.

The A'ama Crab camouflages so well with the black shoreline they're near impossible to spot from even a few feet away. They sit immobile, waiting for the next wave to bring algae and small animals to feed on. Catching them on the camera is a game of patience; the smallest movement or shadow sends them darting into crevasses at insane speeds.

The crabs only emerge after a few minutes of stillness. Move, pause, move, pause, until I was finally close enough to grab a few shots.

Hawaiian locals often cast long lines to fish at the coast. Some leave behind their cut fishing lines, which the crabs must navigate as they wait for food.

The Black Noddy. They roost just under the lips of lava cliffs by the water, sheltered from view. From dusk to dawn the noddies conduct short fishing missions, veering out over the churning water to catch small fish and squid before returning to the colony like a boomerang.

Lava

Every few years, an eruption on the island spills lava flow that burns a miles-wide road to the sea, paving over foliage and entire neighborhoods in Aʻā up to forty feet deep. Kīlauea is the volcano responsible. The world’s most active volcano erupts every few years, with the most recent beginning last December. Not all eruptions are destructive - some are tall fountains of lava that fall back into the crater.

1. Hot steam billows from a vent a few hundred yards from the crater. Plant life is abundant in the area.

2. The Kīlauea crater. Smoke rises from cracks in the center.

3. The path of destruction from the 2018 eruption. A flow that left one long scar down northeastern Big Island, destroying homes in Leilani and Kapoho. The road here was gated off; getting here required pushing through overgrown, derelict pavement until the asphalt and all greenery abruptly ended with the hardened lava pictured above. It stretches to the horizon.

From the land to the sea

The tropical rainforest biome, located on the windward, Hilo side of the island. Here, a bioreserve is built into a rainforest gulch that opens into the ocean. Dense canopy trees and giant ferns fight for every inch of sunlight. Tall Hāpuʻu tree ferns support mini ecosystems, germinating air plants and seedlings in their spongy trunks. Moss covers everything, soaking in the humidity and mist. The smell is dense, earthy, and floral.

Also, bug spray is essential.

Not a forest - a single tree, 400-600 years old. Hanging roots drop from the canopy into the ground, forming trunks and blocking most of the sun. Roots intertwine in the dirt to support the new addition. Walking through here was like walking inside an organism. The ground, the trunks, the leaves overhead, all part of one colony.

The Banyan Tree

The Southernmost point of Big Island, the Southernmost point of the United States. A normally sunny area that turned dark and stormy when I arrived at sunset. High winds whipped the waves into froth as they pounded the coast. In the distance, heavy rain showers obscured the horizon.

Early Polynesian settlers first landed in Hawaii here in 600 CE. They left behind ancient canoe mooring holes and a Kalalea Heiau (fishing shrine), all built from lava rock. Millennia of exposure has worn down these structures, but not their power: Fishermen still leave offerings in the hopes of finding good fishing and to give thanks.

Hell’s Bath

Pololū Valley

Sunrise at Pololū Valley, north Big Island. Unbeknownst to me, Little Fire Ants were crawling up my boots, pants, tripod, and even the wheels of my Jeep while I set up at dawn. Lines of red ants were trundling across the parking lot, the dirt, investigating every inch of the area.

These fire ants are invasive and were introduced to Big Island around 1990. They are rated among the top 100 worst invasive species.

This image was shot on a Canon AE-1 Program with Kodak Gold.

Moses

Sunset on the same day, at the west coast of Big Island. The sun created incredibly tangible rays as it filtered through the trees. I waited for the moment when the calm water collected enough power to send up a splash against the rocky shore.

Windswept

Post-Impressionist Koi